WHO recommends to ‘maintain at least 1 meter (3 feet) distance between yourself and anyone who is coughing or sneezing.’ Governments have translated this into stay-at-home and avoid crowd policies. But what should one do when home itself is a crowded place?

- Vaishali Kushwaha

Happy April Fool’s day! However, let’s not fool ourselves that this COVID-19 pandemic is going to end anytime soon. New York is under siege, Massachusetts (my current residence) will be hitting its peak in the next 2 weeks, and my hometown of Ahmedabad has been just declared one of the 10 hotspots in India. It’s the World War III that Bill Gates predicted!

The current war against COVID-19 virus has once again brought to light the striking social, economic and environmental inequities in our society. In this pandemic where physical distancing has emerged as a key protective measure, urban poor are once again at odds and are unable to protect themselves.WHO recommends to ‘maintain at least 1 meter (3 feet) distance between yourself and anyone who is coughing or sneezing.’ Indian government, like most others, have translated this into stay-at-home and avoid-crowded-places policies. But what should one do when home itself is a crowded place?

Slums by definition are dilapidated, overcrowded residential areas characterized by lack of sufficient living space, lack of access to clean water, inadequate sanitation and insecure tenure1. The 2011 Census reported India’s slum population as 65.5 million (6.5 Crore), which was around 17% of country’s urban population. Let’s consider the current estimated population of 1.3 billion, of which 35% or 455 million live in cities, and of which a conservative 17% still reside in slums.

This converts to an estimated 77 million (7.7 crore) urban poor, i.e. 6% of Indian population, currently living in slums. These are predominantly poor and low-income families, residing in overcrowded and underserviced pockets of Indian cities.Thus at extremely high risk of infection as India edges towards Stage-3 of COVID-19, i.e. community transmission stage.

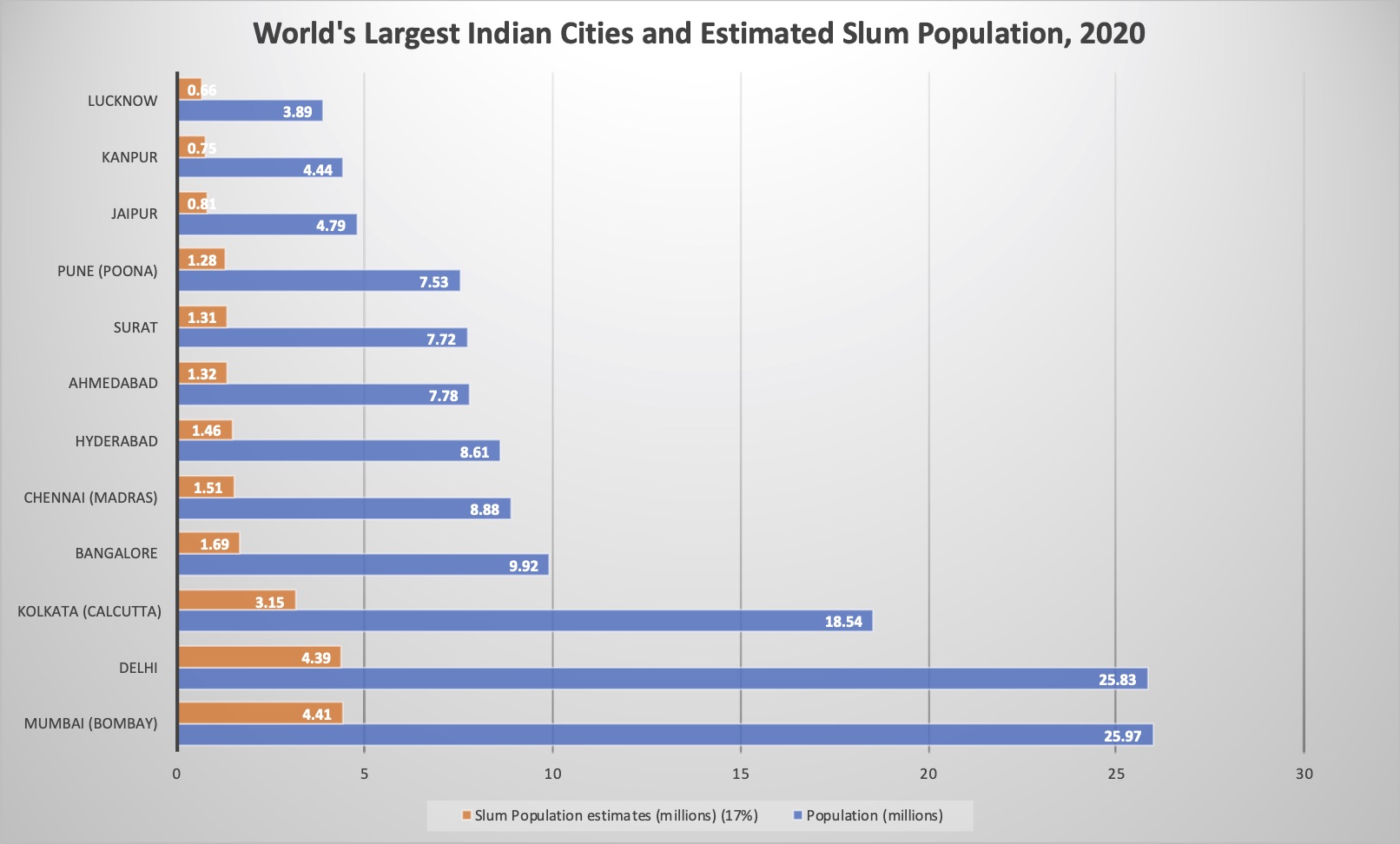

To realize the magnitude of the issue it is important to understand that Indian cities are some of the most populated and densest in the world. Twelve of its cities rank within the top 100 largest cities of the world (Figure 1). Mumbai and Delhi are the 2nd and 3rd largest cities in the world, with population density ranging from as high as 29,650 people per sq. km in Mumbai to 11,040 people per sq. km in Delhi. Slums in Indian cities are even more densely populated, with some areas in Mumbai having density as high as 92,000 people per sq. km2.

How much can physical-distancing or social-distancing help in limiting the spread of COVID-19 in places where a whooping 92 people have to share a square meter of space?

Figure 1. World’s Largest (Within top 100) Indian cities in 2020 and Estimated Slum Population Data Source

|

|

Photos: Slums of India (Location: Ramapir in Chali, Ahmedabad)

A close example of constrained living spaces, narrow pathways, and crowded streets is New York City (NYC). I am aware of the stark economic difference between the two comparisons, but my focus is only on understanding how other densely populated cities/neighborhoods are faring the COVID-19 fight. NYC has a density around 10,726 people per sq. km (27,781.2 people per square mile), which is far lower than any slum settlement and many Indian cities. Nevertheless, New York’s current status as the epicenter of COVID-19 outbreak in the US is being linked to its high density living. Though New York tried to slow the spread of COVID-19 by closing schools, nonessential businesses and urging New Yorkers to stay home – this alone could not stop the exponential growth of COVID-19 infections. As of today, NYC’s COVID-19 confirmed cases were over 45,700 and exponentially rising. Even if India continues its national-level lockdown, this strategy alone will not stop the spread of COVID-19.

Lockdown is only buying us the time to prepare for what is coming next and given the current state of preparedness in Indian cities – it will be a tsunami of COVID-19 positive cases.

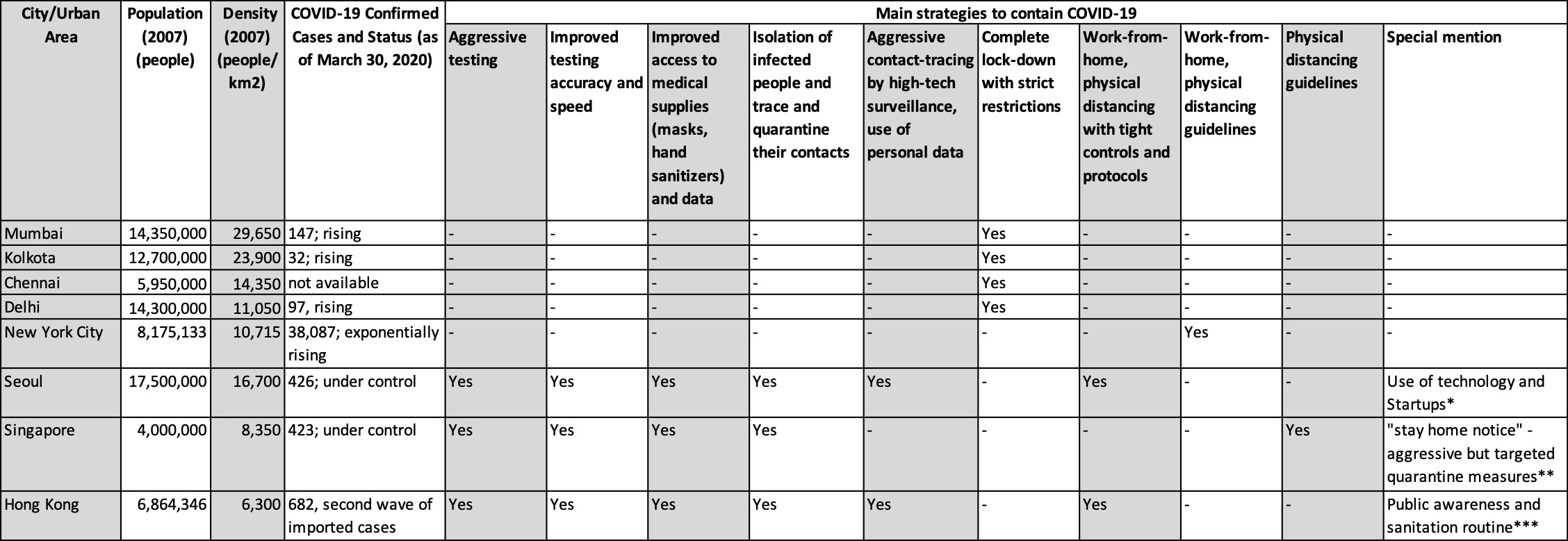

However, NYC is not the only high-density city around the world which has been impacted by this pandemic. Asian cities - Seoul, Hong Kong and Singapore, have emerged as the best practices for COVID-19 control under high density living. Seoul, with its 16,700 people per sq. km density is closer to Indian cities. I compared these large, dense cities, their COVID-19 response strategies and their outcome (Table 1) and found that density alone will not determine fate of Indian cities or it’s slum population.

For high density spaces, in addition to physical distancing,

(1) Aggressive testing, (2) Improved testing accuracy and speed, (3) Improved access to medical supplies (masks, hand sanitizers etc.) (4) Isolation of infected people, (5) and data to trace and quarantine their contacts, are key to ‘flattening the curve’.

Table 1. Comparison of Strategies used to contain COVID-19 in High Density Cities

Sources: City Population and Density

Table 1. Comparison of Strategies used to contain COVID-19 in High Density Cities

Sources: City Population and Density

Currently, local governments in most Indian cities are busy implementing the lock down, managing migrant worker’s exodus and finding ways to deliver food to its residents. Many are busy tackling the present and not preparing for the future. COVID-19 is a very aggressive and sneaky virus, and if city governments fail to predict, plan and tackle the infection at early stages – it will spread across all Indian cities. After synthesizing best and worse planned responses around the world in the high-density cities hit by COVID-19,

I strongly recommend that Indian cities should immediately start building temporary isolation wards. Current COVID-19 guidelines in the US suggest care for yourself at home and seek medical attention when emergency signs develop. This was done to avoid overcrowding and subsequent failure of health facilities. But combined with delayed and lack of aggressive testing, slow contact tracing, and slack in physical distancing, this recover-at-home policy has only added to the community spread of the disease. On the contrary, all the successful Asian cities practiced stringent isolation of infected people (symptomatic and asymptomatic), rapid tracing and home quarantine of their contacts.

In high density slums and neighborhoods where space is a luxury, isolating the infected person (symptomatic and asymptomatic), away from their tiny houses and densely populated communities is the only way to control the spread.

NYC experience shows that even when only severe cases are being admitted, hospitals are running out of beds and wards within the first few weeks of the outbreak. Hence, Indian city officials need to start identifying existing structures that can be rapidly converted into isolation wards. Indian government’s out-of-box thinking of converting train coaches into hospitals on wheels for rural and stressed hotspots is an excellent alternative.

However, at city-level college hostels, dormitories, hotels, convention centers, multi-purpose halls etc. are some of the built spaces that have water, electricity and basic amenities and hence can be rapidly converted into isolation wards.

The US Corps of Engineers is developing site assessment and design/modification guidelines for alternate care sites, and Indian cities can also do the same. NYC is also building an emergency hospital in Central Park in order to cope with the rising number of COVID patients who need emergency care. A similar option for Indian cities would be to start setting up tents and makeshift medical care sites in public grounds, cricket fields, open exhibition and conference venues etc.

India’s per capita medical resources (and monetary capacity) are nowhere close to those of the US, China, South Korea or Singapore. Hence we do not have the luxury of making mistakes and ramping up the efforts at the last moment. Mumbai, Delhi, Ahmedabad and Pune were today identified as hotspots in India.

If Indian cities really want to stay ahead in the war against COVID-19, they have to aggressively plan and prepare for what’s coming next.

We should rapidly learn and customize strategies that have been successful in comparable cities. Government, with support of the private sector and civil society, needs to provide free COVID-19 testing, personal protection supplies (masks, hand sanitizers, hand soaps, water in portable containers, cleaning products etc.) and access to isolation units to the vulnerable urban poor.

Update 4 April 2020: With the number of Covid-19 cases across India spiking in the last one week, National government recommending states to adopt the ‘Bhilwara model’ of ruthless containment. In this successful containment startegy quarantine facilities were also ramped up. Apart from the dedicated Covid-19 hospitals,

the district administration took over and converted into quarantine centres four private hospitals, each having 25 beds, as well as 27 hotels with 1,541 rooms. At present, 950 people are in quarantine centres, while another 7,620 people are in home quarantine.

Best Practices: Special Mention (Table 1)

[1] Seoul: Use of Technology and Startups*

[2] Singapore: “Stay Home Notice” – Agressive but targeted quarantine practices**

[3] Hong Kong: Public awareness and sanitation routine ***

-

“Slums are those residential areas where dwellings are in any respect unfit for human habitation by reasons of dilapidation, overcrowding, faulty arrangements and designs of such buildings, narrowness or faulty arrangement of streets, lack of ventilation, light, sanitation facilities or any combination of these factors which are detrimental to safety, health and morals.” – Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Handbook of Urban Statistics 2019 ↩

-

Density estimates for Mumbai’s G North municipal ward, that houses the world-famous Dharavi slum, is around 66,000 persons per sq. km. Whereas, the most crowded municipal ward in Mumbai is Ward C with whooping density of around 92,000 per sq. km. ↩